South America’s geography is unique. The western portion is dominated by the Andes Mountains running from just south of the Isthmus of Panama to the southern continental tip, a distance of 7,240 kilometers (4,500 miles). The Andes feature some of the highest mountains in the world with dozens of peaks exceeding 6,100 meters (20,000 feet) in height. Many of the continent’s great rivers flow from the Andes to the Atlantic. Others have sources in the Brazilian Shield and Guaina Highlands. On the Andes western side glaciers feed mountain lakes and thousands of small rivers and streams that rapidly descend into some of the driest terrain in the world before reaching the narrow Pacific coastal plain. These rivers are short and sharp unlike the ones that dominate the rest of the continent largely flowing from west to east or south to north. Among these are the Parana-Paraguay, the Sao Francisco, the Amazon, the Orinoco and the Magdalena.

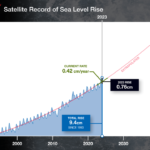

Climate change is impacting South America particularly in the tropical Andes. The mountains of Peru, Ecuador, and Columbia straddle the equator and contain 99% of all tropical glaciers in the world. Over the last 50 years this region has experienced unprecedented change. With a mean warming of 0.7 Celsius (1.26 Fahrenheit), and no appreciable change in precipitation over the last 50 years, has come considerable alpine glacial melt. Total shrinkage has amounted to between 30 and 50% since the 1970s with glaciers below 5,400 meters (17,716 feet) melting at twice the rate of those above that elevation. These glaciers are important sources of freshwater for much of Peru, Bolivia, Columbia and Ecuador. La Paz, one of Bolivia principal cities, has experienced a reduction in glacial freshwater. The city relies on the ice fields for between 15 and 27% of its annual water supply.

A good example of the impact of deglaciation on rivers flowing west into the Pacific is the Rio Santa. Only 316 kilometers (196 miles) long, it arises in the Cordillera Blanca to the west of the main Andes chain and then after coursing through mountain valleys takes a sharp turn while descending to the Pacific Ocean. The river valley (see map below) has seen as much as a 22% reduction in glacial mass (the blue sections on the map) in the last 40 years. The valley itself, about one-third the size of Switzerland, serves as home to 1.8 million people. The instability of the glaciers feeding the river is an ongoing problem. In 2003, for example, a crack appeared in a feed glacier that creates one of the alpine lakes. Valley inhabitants were warned about a potential glacial flood burst which the local call aluviones. In 1941 one sudden deglaciation event of this type killed almost 7,000.

But if Peruvian glacial melt affects rivers flowing into the Pacific, how will it impact rivers flowing to the Atlantic? The monster river of South America is the Amazon, the largest freshwater source on Earth. Only the ice fields of Antarctica and Greenland hold more water.

The Amazon arises in the Peruvian Andes not far from where the Rio Santa begins. But the Amazon flows east descending into a basin with the largest continuous rainforest on Earth. The total drainage area amounts to more than 7 million square kilometers (2.7 million square miles). Seen in the map below, the Amazon and its many tributaries derives its initial water volume from glaciers but rain in the Basin adds to the river’s immense flow, representing close to 20% of all the water found in the world’s rivers.

As can be seen from the above map of the Amazon watershed, the Andes play a significant role in the river and its many tributaries. Deglaciation that affects the Rio Santa will also impact the Amazon. But instead of 1.8 million being impacted with the former, we are talking about 20 million in the latter combined with 10 million different species of animal and insect life, and 56% of the world’s broad leaf forests. With decreased glacial mass outflow over time will decline. Today the fertility of the Amazon Basin relies partly on the sediment deposited from flow output arising in the Amazon’s Andes tributaries.

One thing scientists concur on is the important role the Amazon basin plays in global climate stability. The basin’s rainforest serves as the largest carbon trap on the planet sequestering about 20% of the CO2 we humans emit from burning of fossil fuels. The river produces 20% of the planet’s fresh water. Evaporation of this water and subsequent condensation is key to regulating global climate. And since the Amazon creates between 50 and 80% of its own rainfall through the water cycle, what would happen if human activity plus climate change were to disrupt this?

One of those human activities is deforestation. Deforestation is having an enormous impact. In 1995 when deforestation was at its peak in Brazil, over 25,000 square kilometers (9,675 square miles) of forest were lost each year to illegal logging. Today that rate has declined because of policing but it still goes on. What does it mean when you cut down a tree in the Brazilian rainforest? One tree delivers 1,000 liters (264 U.S. gallons) of water to the atmosphere every day. The amount of water vapour the forest gives up has been described as a flying river. And this flying river impacts all other regions of South America east of the Andes Mountains. Amazon-forest water vapour feeds the Parana-Paraguay, the Sao Francisco, and the Orinoco River systems.

So tinkering with the Amazon affects much more than the basin itself. Now you are playing with global weather as well as the rainfall for almost the entire South American continent. Today scientists estimate that 20% of the Amazon rainforest basin has been destroyed. Brazil has become a net greenhouse emitter despite the fact that it holds within its boundaries the largest carbon trap on the planet.

[…] More here: South America's rivers are extremely susceptible to climate change. […]

[…] South America's rivers are extremely susceptible to climate change. […]

According to a new study of ground-based rainfall measurements over the past 30 years, the Southern Amazonia is witnessing longer dry seasons. The average increase has been one week per decade. This has led to an increase in the length of the fire season, a threat to the Amazon forests. What is more frightening is that current IPCC models which predict longer dry seasons are not as extreme as the reality. Of course the likely cause is increased greenhouse warming blocking fronts that would trigger rain. A longer dry season may accelerate the decline in the Amazon rainforest with implications for the entire globe should that occur. For more go to the article at: http://www.scienceworldreport.com/articles/10383/20131022/risk-amazon-rainforest-dieback-higher-predicted-dangers-climate-change.htm.