If you live in a rice-growing region today and are largely dependent on it as your biggest source of daily calories, your food security is already compromised. Rice is proving to be particularly vulnerable to global warming, with 17% of rice production today being affected by the existing rise of 1.55 Celsius (2.79 Fahrenheit) in mean temperatures above pre-Industrial Revolution levels. Offsetting crop production declines in these rice-growing areas will be expansion into mid to high-latitude farmed areas. Today, these are areas where corn and wheat are grown as staple crops, not rice.

With 2024 seeing us hit the 1.55 Celsius increase mark, it means for low-latitude regions of the planet, between a 10 and 48% drop in crop yields. These are areas of the planet with the most rapid growth in human population. Particularly affected are the Sub-Saharan countries of Africa including Niger, Mali, Somalia, Angola, Tanzania, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda and Ethiopia with population annual growth rates of between 2 and 3%.

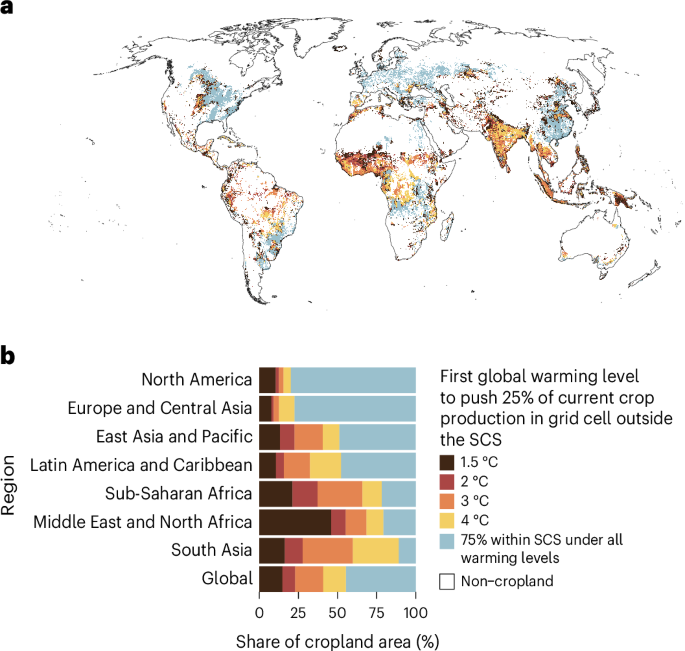

The journal Nature Food published on March 4, 2025, an article entitled, “Climate change threatens crop diversity at low latitudes.” The authors from Aalto University in Finland, the University of Göttingen in Germany, and the University of Zürich in Switzerland analyzed 30 major food crops being grown and their spatial distribution in low-latitude countries. They forecast that under 2 Celsius (3.6 Fahrenheit) of global warming, up to 31% of staple crop production land would be lost, with food diversity declining by 52%. If warming rose by 3 Celsius (5.4 Fahrenheit), there would be an up to 48% decline in the former, and 56% in the latter.

With rice, wheat and corn, and two other staples, potato and soybean, accounting for more than two-thirds of the world’s food energy, and cassava, yam and cowpea making up much of the rest, the world’s poorest countries will increasingly face a food security crisis.

Sara Heikonen, described the degree of peril to SciDevNet writer, Claudia Caruana, “In Sub-Saharan Africa, the region which would be impacted most, almost three-quarters of current production is at risk if global warming exceeds three degrees Celsius.”

Considering the ineffectiveness of collective climate change mitigation efforts to date, the imperative for agronomists is to develop new varieties of these staple crops and identify other plant species that are more warming and drought-resilient but currently underplanted and underutilized.

In 2021, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations noted that 500 million smallholder farmers with less than 2 hectares (under 5 acres), and mostly located in the areas described above were responsible for producing 35% of the world’s food. These are the operations deemed to be at greatest risk.

Some academicians, such as Kyle Davis, a professor of geography and spatial sciences at the University of Delaware, argue that farmers, historically, have proven to be innovative in adapting to a changing climate. He stated that, “Many of the tried-and-true methods used by farmers will likely play an important role in determining future patterns of food production, including selective breeding … irrigation, switching crops to more climatically suitable varieties, and incorporating the benefits of natural systems.”

What Davis doesn’t describe is how marginal farming is impacting smallholder farmers. For example, from 2014 to 2023, 100,474 farmers in India with holdings of less than 2 hectares committed suicide. The main causes included crop failures from droughts, floods, pests, weather and climate change, as well as indebtedness, and inadequate government support.