March 15, 2019 – With space tourism about to begin, we are no longer in an age where those going into space will be monitored a thousand ways to ensure they are healthy throughout a flight. Paying customers are lining up to ride on commercial space company hardware to the edge of our atmosphere and beyond. Whether that ride involves Virgin Galactic, Blue Origin, Sierra Nevada, Bigelow Aerospace, or SpaceX, those entering the near vacuum of space will not be the highly trained, regulated, and scrutinized astronauts, cosmonauts, and taikonauts of the past. These will be people like you and me albeit with more money than they know what to do with.

Paying customers won’t be asked if they have preexisting medical conditions when they put down their quarter million dollars or more to ride a rocket or rocketplane. Yet there will be inherent risks involved for anyone choosing to subject themselves to the forces of gravity felt in lift-off and re-entry, and to the near weightlessness in the microgravity of space.

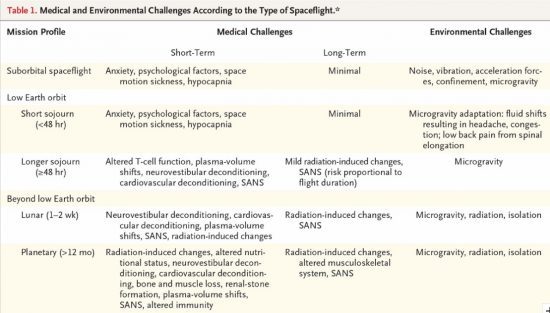

What this means for medicine is an entirely new field of practice. In the March 14, 2019 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, it describes the challenges humans will face in spaceflight including changes to our physiology as well as psychological challenges. The table that follows provides a list of all the risks space tourists will be exposed to from suborbital flights to visits to the International Space Station (ISS), to missions to Deep Space, the Moon, and Mars.

Depending on the type of trip space tourists take they will experience challenges never faced here on Earth.

Launch alone will expose them to the G-forces of powered ascent, excessive vibration and shaking, and noise greater than any rock concert.

In a sub-orbital flight, the exposure will be minimal. But in low-Earth orbit, space travelers will experience the disorientation of weightlessness and the lack of gravity references to up and down. This leads to motion sickness, nausea, vomiting, headaches, and problems with hand-eye coordination.

A prolonged stay in near-weightlessness will change the way fluids behave in our bodies leading to puffiness in the upper extremities and face, congestion, urinary retention, and even more headaches.

Although our heart and lungs adapt to the weightless environment, our bones and muscles do not. For example, prolonged exposure to weightlessness causes the bones to demineralize (osteoporosis) and our spines to lengthen. With a pre-existing condition of osteoarthritis, space doctors may have to treat increased incidents of chronic pain or increased risk of spinal disk herniations.

Even our body organs will shift as we experience prolonged weightlessness including the movement of our diaphragms upward which may or may not contribute to shortness of breath.

And what about allergies? If a space traveler has them on Earth, will they manifest differently when in space?

Sleep patterns will be altered in weightlessness not just because of the physiological changes that will happen to our bodies, but because in orbit we will experience day and night every 90 minutes.

For long missions such as those contemplated for a trip to Mars lasting up to 180-days outbound, 30 or more days on the planet surface, and 180-days coming back, the psychology of long duration near isolation presents a real challenge. Even in shorter-duration space flights the unusual environment of space will create anxiety and unpredictable behaviour from space travelers. Imagine then what a prolonged trip will do to our human psyche.

Unlike the rigorous screening process that NASA, Roscosmos, and China’s Space Agency have used to select candidates for spaceflight based on compatibility, those operating commercial space tourism will do only limited screening of passengers and will provide rudimentary orientation before each trip. Think of how we are treated when we fly and you get the picture. What is the orientation we receive? Where to park our luggage in the overhead bin or the area below the seat in front of us, how to buckle our seat belts, where to find the emergency exits, and how to use the oxygen masks and life vests.

And should a medical emergency occur on flights beyond low-Earth orbit, there will be little anyone on board can do for the affected passenger. It won’t be like we will be flying on the ISS where there is medical support available not only from a team of doctors on the ground, but also onboard medical supplies including diagnostic and imaging tools, medication and storable blood products. And those on the ISS receive extensive emergency medical instruction before flying, with from time to time a doctor as one of the crew. That won’t be the case with space tourism. In the event of an emergency getting back to the surface will be the protocol.

That won’t be the case when we venture into Deep Space. Relaying medical advice from the Earth to the Moon experiences only a few seconds delay. But on a journey to Mars, the latency of long-distance communications will mean it could take up to 20 minutes there and 20 minutes back to deal with a medical emergency onboard.

Finally, there is the issue of cosmic and solar radiation for any Deep Space voyage that takes us beyond the safety of low-Earth orbit. We know from the Curiosity rover’s outward bound voyage to Mars that a space traveler making the up to 180-day journey will be exposed to as much radiation as 24 CAT scans, 15 times the acceptable annual radiation limit for those who work in nuclear power plants. The impact on our immune system, cell division, and overall physiology remain unknowns.

As the Federal Aviation Administration rolls out policy for space tourism it needs to establish flight rules. Will they be different from those that govern civilian airline travel? Probably not. The decision to fly will be a burden placed on the traveler who will receive an information packet requiring informed consent before getting onboard. But even the commercial companies offering space travel services have yet to anticipate all the risks present in space flight. I would expect a whole new area of injury law to emerge. And practicing physicians will find themselves in unfamiliar territory as new space-related medical conditions become more common.