An article in today’s Globe & Mail by Shaun Pett got me thinking about our heavy reliance on annual staple crops to feed the world and the cost we bear because of this. Annuals are labour intensive. They involve plowing the soil every year and seeding. They are responsible for 70% of the food calories we humans and our animals consume. And their management and cultivation contribute to greenhouse gas emissions amounting to 24% of the total.

In the article Pett states that we fell into this trap 10,000 years ago at the dawn of the Neolithic when we chose annual grains, legumes and oil seed crops to be our main source of plant nutrition. The result today is agricultural practices that are problematic with Pett in his article providing some statistics and challenges that we face because of our reliance on annuals:

- today 70% of the food calories we consume come from these types of crops;

- growing annuals for food contributes 24% of the greenhouse gases we produce globally;

- deep plowing for planting annuals contributes to soil erosion;

- or the alternative no-till planting requires lacing soils with enough chemicals to inhibit weeds and competitive plants.

At the Land Institute in Salina, Kansas, researchers are looking at ways to alter our dependence on annuals by developing perennial versions of the plants we grow for food. For years I have planted a perennial garden rather than annual flowers. I have done this even at our new apartment downtown here in Toronto, planting perennials in pots rather than the typical flowering annuals. Why? Because perennials seem better equipped to handle environmental changes. They persist under the most difficult conditions. If it is too cold in the spring they tend to be self inhibiting waiting for the weather to improve. And they seem to be less demanding about soil conditions or needing artificial fertilizers. A good mulch cover in the fall works wonders.

The researchers at the Land Institute believe that perennial grains, oil seed crops and legumes can be developed reversing 10,000 years of agricultural mistakes made by us. They are doing this in two ways:

- discovering wild perennial plants with the best crop potential and domesticating them;

- or cross-breeding annuals with related perennials to create new hybrids.

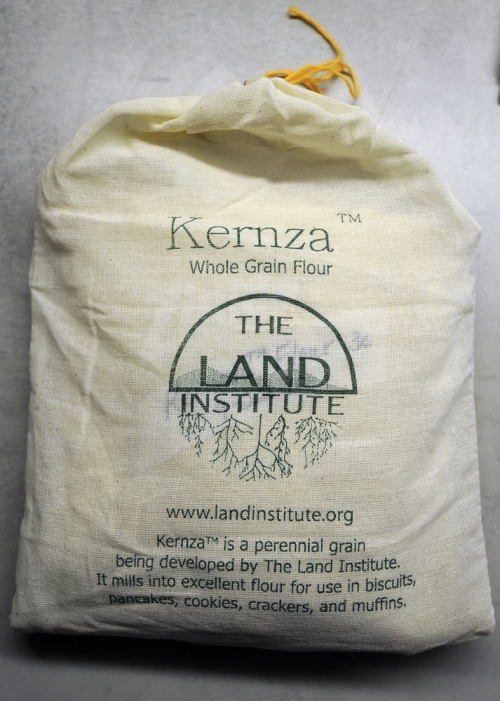

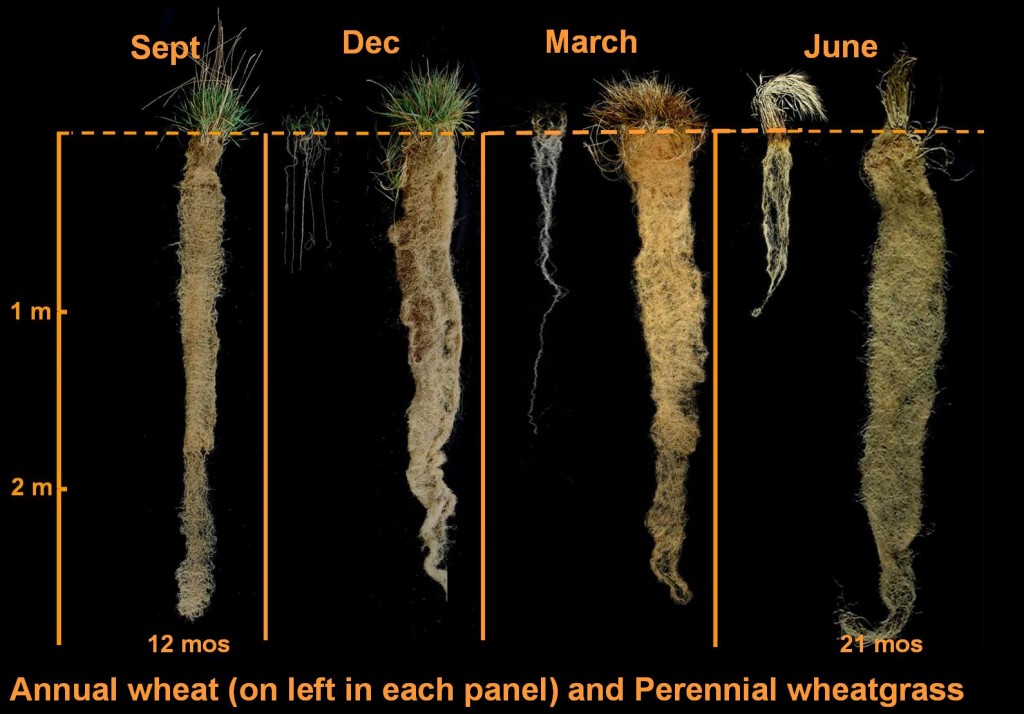

The hope is to release the first perennial grain crop within a decade. The Institute is currently developing a wheat grass called Kernza. It looks a bit like wheat but like most perennials it grows more slowly. It develops extensive root systems (see image below) which hold the soil in place and retain moisture. It shows high variability when planted so a Kernza field isn’t as pretty as the wheat fields you see on the Prairies today. But it provides continuous coverage so the soil is not exposed to erosion. It needs less tending and as a bonus provides winter fodder for native and herding animals without losing its viability to propagate and produce subsequent harvests.

The Institute has been developing Kernza for 7 years and has harvested the crop to produce flour “excellent for use in biscuits, cookies, crackers, and muffins.” The yields to date are far less than those produced by annual wheat but the researchers believe they will soon match wheat in future harvests.

And Kernza is proving to have other unique benefits. Its protein content per kilogram is 20% higher than wheat. It produces more fibre, double the level of omega-3 fatty acids, five times the calcium and ten times the folate.

Other perennial projects at the Institute include development of a perennial variety of sorghum as well as perennial sunflowers.

Is the Institute unique in pursuing perennial crops? Hardly. We’ve been growing them as food sources for years. After all fruit and nut trees, bananas, palms, breadfruit, and avocados are all perennials. Several types of perennial beans and tubers provide staple crops for many tropical and subtropical countries. But none of the above equal the volume of food we get from grains like wheat and rice, two of the dominant agricultural crops grown on this planet. We can, however, learn from our experience in cultivating perennials, ways to develop even more choices and in the process reduce the toll we are putting on precious top soils and fresh water while feeding the planet.

This article was a real eye opener for me. I hadn’t considered that our crop choice could be perrenial , I just assumed that we would need to replant each year. The benefits of new strains of perrenial crops looks to be huge. I would be think this approach would completely change agriculture. We would need to think about how the economy would adjust to such a shift, but i believe we have time to understand those effects.

Hi Steve, We forget that our agriculture choices have been dictated by history. A reliance on annual crops that really started with domestication of wheat grasses in the Fertile Crescent of Southwest Asia soon migrated through the Mediterranean World and with the later dominance of Europe and the West became the defacto choice for staple crops. Similarly rice became the staple of East Asia largely driven by the dominance of Chinese culture in the region. These were cultural rather than science-based choices. Science, however, can serve to alter 10,000 years of poor decision making if we can create perennial strains of our common staples.

Hi Len;

The perennial proposition is very interesting, and also extremely complex. Implications are manifold. I’m thinking we should be very cautious before we implement basic starch food production with “engineered” perennials. If it proves out to be more profitable than annual tillage systems, then most of global agribusiness will rapidly convert to it, and all the traditional tillage technology and support industries will fall into disrepair. So far so good, but what happens if something like the great grape blight of the mid 1800s hits the newly established perennial starch plant’s roots?

The great grape blight, a fungal infection of perennial grapevine roots spread by billions of tiny aphids from the Americas, swept through Europe like the plague, millions of acres of vineyards with centuries-old vines were infected, and nearly every grapevine in France died. So did many centuries-old winemaking businesses, and thousands of the poorly nourished field worker’s children starved. The only solution was to dig-out and burn all the infected old world rootstock, replace it with new world rootstock, and then graft the old world vines onto the new world roots. Several years passed before wine production could be restored. The wine produced from the new world roots has a different character than the wine produced from the old world roots. Some of the old world rootstock and vines still exist today in the nation of Chili, from which very excellent vintages similar to ante-blight European wines are produced. A wonderfully beautiful, highly allegorical, somewhat bizarre, heart-wrenching, dramatic movie titled, “Heavenly Vintage,” accurately depicts the great grape blight epoch and is available on streaming Netflix.

A global civilization of some seven billion hominids could likely comfortably survive 4-5 years of serious wine shortages, but how would it fare with 4-5 years of serious starch shortages? Say the world plants 10% of its starch crops in engineered perennials, and then if the crops fail the world has to tighten its belt by only ten percent, which in most of the developed world might be a good idea anyway. The major problem would be if the 10% perennials turn out to be more profitable than the traditional tillage starches. The temptation to constantly increase the perennial percentage would prove irresistible.

I would think that we will see multiple grain perennial varieties developed to mitigate against the risk of a blight overwhelming a single homogeneous species approach. It never pays to put your eggs all in one basket. But you bring up an interesting historical reference. A similar challenge happened with bananas and may happen to that fruit in the near future. The song, “Yes, We have no Bananas” is an historical artifact of a period of time when a blight destroyed the predominant variety. The banana we eat today are mainly two varieties, one called Cavendish and the other called Nain. Right now a number of fungi are beginning to impact these crops. I know that some will be upset but the answer to thwarting the fungi will probably be introducing genetic engineering to provide resistance. That means another GMO on grocery shelves.

[…] forests. Today there are no perennial grains in widespread use. Back in 2013 I wrote about Kernza, a perennial wheatgrass being developed as a wheat substitute by The Land Institute in Salina, […]