June 2, 2019 – Last year Germany’s Bayer, the company that acquired Monsanto, and Ginkgo Bioworks, a spinout from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, formed a joint venture to change the bacteria found in the root systems of cereal crops, the primary diet of most humans on this planet.

Why?

The new joint venture, which was given the name Joyn Bio, is tasked with engineering bacteria that is symbiotic with the primary cereal crops grown today – corn, wheat, and rice, to dramatically decrease the fertilizers used in farming.

Why is this needed? For two very good reasons.

- The bacteria normally associated with cereal crops do not fix nitrogen in the soil for plant health.

- The fertilizer used to provide nitrogen to cereal crops is derived from fossil fuels in a highly-polluting process.

Creating nitrogen-fixing microbes friendly to cereal crops would mean:

- A reduction in the use of synthetic fertilizers in agriculture.

- Less methane escaping into the atmosphere during fertilizer production, and less nitrous oxide emissions, both potent greenhouse gases.

- Cleaner freshwater both above and below ground with less synthetic fertilizer runoff entering lakes, streams, and eventually underground aquifers.

- Fewer algae blooms and dead zones in our oceans and lakes from concentrations of synthetic fertilizer chemical runoff.

Many oppose genetically modified anything, the science and engineering whereby genetic information is altered within a species not by selective breeding but by changing its DNA. The typical opposition calls alterations to foods we would normally eat, “frankenfoods.” But what if we genetically modified the bacteria in and around the root systems of plants, bacteria that provides symbiotic benefits to plants like cereal crops? Would opponents to genetic modification consider this to be a Frankensteinian move?

In the announcement of their joint venture, Bayer and Ginkgo Bioworks, the two indicated their purpose to develop synthetic biology to support sustainable agriculture, and that their first project was to deal with environmental impacts from synthetic nitrogen-based fertilizers.

Plants and their Symbiotic Microbes

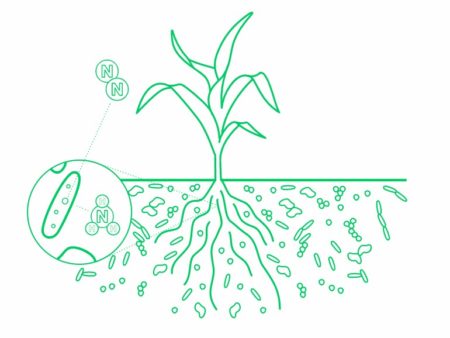

Every plant has a symbiotic relationship with a microbiome consisting of hundreds of different bacteria that occupy the soil near its roots. In the case of cereal crops, the microbiome is not particularly good at fixing nitrogen from the air to make it useful to plants. You see, even though most of our atmosphere is made of nitrogen gas, nearly 80%, the problem is plants, for the most part, cannot absorb it from the air in its existing form. That’s because atmospheric nitrogen contains two atoms of the element bonded together, and most plants cannot break the bond to absorb a single nitrogen atom.

But the scientists at Bayer have an extensive library of microbes found in and around plants, and they have identified those that have a symbiotic relationship with legumes – soybeans, peanuts, alfalfa, and peas, have the ability to take nitrogen from the atmosphere through normal biological processes.

So Joyn Bio’s task will be to use the existing bacteria common to cereal crops and switch out the genetic machinery inside with that of the legume symbiotic microbes. If successful it would mean for the first time, cereal crops would no longer need to use nitrogen fertilizers to the extent they are being used today. The Joyn Bio team of researchers believe, if successful, they can reduce global synthetic fertilizer use by 35%. And that means a lot less nitrous oxide emissions, algae blooms, ocean dead zones, and global heating.

Creating synthetic biology isn’t simple.

First, you have to identify which cereal crop microbes would be the best candidates to fix nitrogen.

Second, you have to identify which are the nitrogen-fixing genes in the legume microbes that you need to emulate or borrow.

Third, you have to engineer the cereal crop microbial DNA to make it work the same way the legume microbe DNA works.

Fourth, you have to ensure that what you have created replicates, remains stable, and can thrive in the microbiome environment found around cereal crop root systems.

Joyn Bio calls what they are attempting to produce, probiotics for plants. If successful they believe they can cut worldwide global greenhouse gas emissions by 3%, and reduce natural gas usage also by 3%.

For those opposed to genetically modified anything, I wonder what will be their take on this joint venture?