What made me want to write about this subject was an electric clothes dryer that started smoking in our apartment when my wife turned it on a few days ago. She called me over as she watched what appeared to be the drum taking on an unnatural glow. Of course, being the knowledgeable male in our mated pair, I didn’t take her word for it and tried the dryer myself. Doing the same thing twice or more and getting the same results convinced me that we had a problem.

One thing about electric clothes dryers, they appear to be built to fail, particularly the smaller models that fit on top of washing machines in stackable configurations. The dryers have small capacity, produce a ton of lint that constantly needs to be cleaned out from traps and exhaust vents. I would bet that the lint problem is half the reason these dryers fail.

Now we are renters and our stacked washer and dryer have presented problems in the past. First it was the washing machine that went. We couldn’t find a matching model to go with our stackable dryer. The result was having to improvise a stable stack of machines from two different manufacturers. We did find a solution and the machines have been fine for the last few years until this week when the dryer had its turn to fail. First, we tried to find someone to fix it. We found someone who unfortunately was unvaccinated for COVID-19. Just another complication in this pandemic scenario in which we are living.

So the alternative was to source a new dryer that would be compatible with our washing machine or could be stacked on top of it. We found one but from another manufacturer. I explained the situation to the supplier but when the shipper and installer came to our place (fully vaccinated I might add) the installation was a no-go. The reason given was that stacking machines from two different manufacturers would invalidate the warranty. When I called the supplier we were told that if the machines were mated securely the warranty would be honoured. Since we had managed to do that with two different manufacturers’ machines for the last five years, the remaining challenge was to find someone to replicate the workable solution we had produced in the past. Our alternative was to buy a matching washing machine to go with the new dryer. But that would have meant throwing out a perfectly good machine that was less than five years old and in perfect working operation.

The experience has got me thinking. How often does this happen when purchasing a washer-dryer stackable combo? How often does one machine go before the other and create a similar circumstance to the one we have experienced?

Is our circumstance the fallout from a global manufacturing model built around planned obsolescence, which by definition is the creation of new products designed to have short life expectancies to make consumers have to buy anew?

This is not my first experience of the past year with planned obsolescence. My wife’s smartphone seems to have been built to fail. When we recently visited our telecommunications provider, the answer given to all of its technical eccentricities and behaviours was to get a new model, hint, with one going on sale at Christmas.

Our vacuum cleaner, a Dyson stick less than five years old which we maintained to the manufacturer’s specifications, has now had to be replaced because of motor problems making repairing almost as costly as buying a new one. And so we have done the latter.

Then there’s my laptop, a Chromebook that has served me well to write this blog when we travel and is the backup to my desktop system. After the last update, I received a message from Google stating no further operating system updates would be available for the machine because the model’s processor was obsolete, still working mind you, but nevertheless now a dinosaur.

It has even happened with my Dell desktop system where I have invested in multiple screen displays, two terabytes of external hard drives, and more. Why? Because the newest Windows operating system about to be released is incompatible with my machine’s central processor making it impossible to do the upgrade. This leaves me to ponder how much longer the older Windows operating system will continue to be supported by the company for a hardware investment that is five years old.

I used to think the automobile industry’s annual new model rollouts were the paradigm of planned obsolescence, but no longer are they alone in manipulating consumers to make expensive purchases unnecessarily. Being forced to spend money on technology made incompatible or too expensive to repair by manufacturers is angrifying. Nor should we have to endure the challenges of dealing with washer-dryer stacks where one machine fails and a compatible mate from the same manufacturer no longer exists forcing you to buy two machines rather than one.

What do planned obsolescence and the premature discarding of technology cost society and the planet?

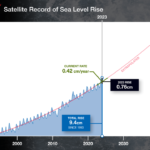

An article appearing on the website Climatalk states that in 2019, electronic waste amounted to 53.6 megatons globally or the equivalent of 7.3 Kilograms (over 16 pounds) per person. That amount was expected to rise to 74.7 megatons or 9.0 kilograms (almost 20 pounds) per person by 2030.

How much of our electronics end up in landfills? How much is repurposed, or recycled? How much material recovery is done from old electronics? And how much of this could be avoided by eliminating outdatedness in manufacturing and by extending the lifetime of the products we buy.

In my search for answers, I leave you with some interesting statistics to contemplate.

- Perceived product ageing has 15% of smartphone buyers replacing perfectly good models in less than 2 years even though manufacturers admit that the products are built to last on average 5.2 years with the lithium battery being the chief longevity delimiter, not the electronics or software.

- 72% of the global warming potential of today’s smartphones stems from their production, transportation, and disposal.

- 17.4% of electronic waste today is collected and recycled meaning the bulk of materials used by manufacturers has to be sourced anew.

- Mining industries produce 25% of global greenhouse gas emissions of which a sizable portion of material output goes into electronics.

- Waste toxicity from discarded electronics is an ongoing problem, in particular lead and mercury which are found in landfills and can leach into groundwater and local surface waters.