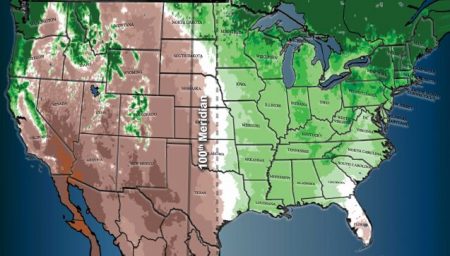

Americans continue to migrate from the Northeast to the South and Southwest. As the country’s population ages, seeking warmer climes for aching bones is hardly surprising. But freshwater sources can’t pull up roots and resettle the way humans can. The country may be divided in its politics by red and blue states, and by coastlines versus the heartland, but climatologically it is the area to the west of the Mississippi River that is the new environmental divider separating a wetter east from a drier west (see map image below). And that divide is becoming more exaggerated as the atmosphere continues to warm causing an even wetter east and drier west.

The Great Plains states of the U.S. after the Dust Bowl 1930s, have become the country’s breadbasket. Irrigation, not nature is the reason. Tapping into aquifers (underground water sources) has turned marginal grassland into fields of corn, wheat, soybeans, canola and more. A water source, the Ogallala Aquifer, stretching from Texas through Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, and the Dakotas has transformed the land. Last year this vital water source for agricultural irrigation reached its lowest water levels since NASA began mapping it by satellite.

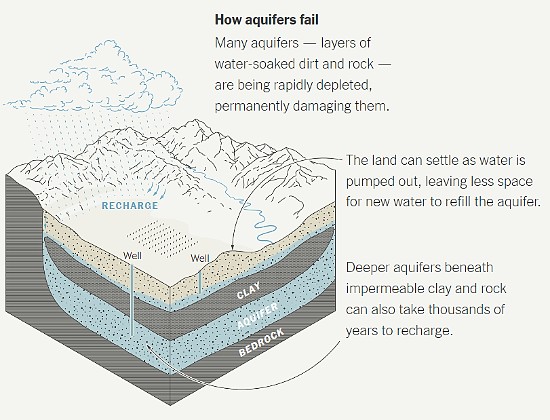

California, Nevada, Arizona and other dry states pumped water from underground aquifers and channelled it from the Colorado River to turn scrub and semi-desert into productive fields. The aquifer under California’s Central Valley has made that state the market garden capital of the country. Aquifers, however, can be drained through excessive water demand, and droughts can make surface water sources unreliable.

With all these challenges on the western side of the Mississippi, shouldn’t officials in county, municipal, state and federal jurisdictions in those areas most affected by the growing water shortage be advising and discouraging migration? For the most part, though, the people in charge of the western half of the nation seem oblivious or unconcerned about their rising population when combined with depleting freshwater sources.

According to David Gelles who has recently written about it in the New York Times, aquifers responsible for supplying 90% of the country’s freshwater are being depleted with reserves “drying up in a matter of years.”

Back in June of this year, Phoenix, Arizona told developers of new subdivisions that there were insufficient groundwater resources to meet future population growth. Phoenix was supplementing aquifer-based sources by drawing from the Colorado River. In both cases, the water supply was dwindling. The city forecast its groundwater sources would fall by an average 56 metres (185 feet) over the next 100 years. As a result, the city told developers that no new housing builds would be approved without accounting for the freshwater needs of subdivisions with water guarantees lasting 100 years into the future.

In California’s Central Valley even with the recent tropical storm that dumped record levels of rainfall, the prolonged drought continues to be evident with the valley floor subsiding from 1.25 to 3.65 metres (4 to 12 feet) because of overdrawing from the aquifer.

Law professor and water expert, Warigia Bowman, at the University of Tulsa notes that “There will be parts of the U.S. that run out of drinking water.”

Pumping groundwater appears to be doing more than just causing communities to run out of existing freshwater. New research links the depletion of aquifers to changes in the Earth’s polar motion.

What is polar motion? It is a periodic rotation of Earth’s spin axis that differs from the mean or fixed axis at 90 degrees north and south latitude. Unlike the fixed axis, polar motion causes a 6.5-year periodic wobble as Earth spins. The path of the polar motion traces around the mean axis.

Groundwater depletion appears to be a significant contributor to changes in two wobbles that characterize the polar motion path. Scientists who first observed these changes thought the polar motion changes were associated directly with the melting of polar land and sea ice. But now they have compelling evidence that links groundwater depletion from human activity to subtly changing the Earth’s shape and thus the wobble. Earth is a spinning top that is being further excited by us taking more and more groundwater from beneath its surface. It is not yet enough to affect seasonal changes but if we continue our current behaviour could one day add another twist to the tale of human activity linked to climate change.